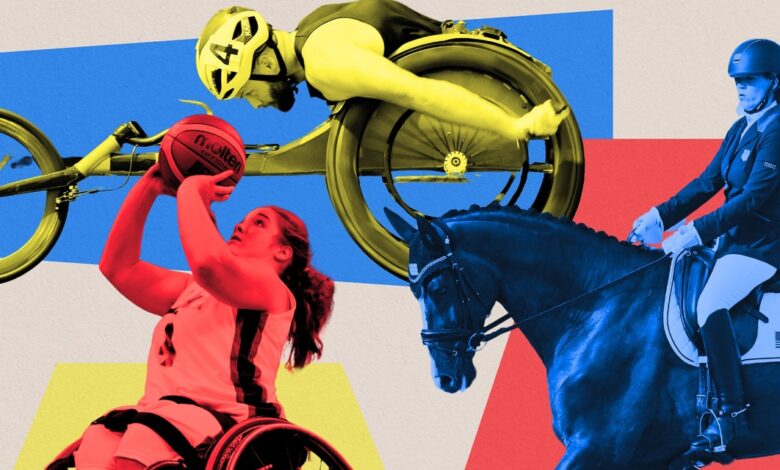

It Shouldn’t Be This Expensive to Be a Paralympic Athlete

Just weeks before the Paralympic trials in early July—the only qualifying event for para-cyclists to earn their spot on Team USA—the back of Kate Brim’s handcycle cracked so badly she didn’t know if she would be able to compete, much less make the team. Although a temporary fix got her through the event and a spot in Paris, the 26-year-old found out the frame needed to be replaced before she could head to the Games just two months later.

A broken frame might not seem like a huge deal, but when it costs $8,000 to repair, it sure does become one. Brim is paralyzed from the waist down and has limited mobility in her hands due to complications from a surgery when she was 19, so her bike is specifically constructed to meet her needs—which explains the hefty price tag. This year alone, Brim says she has spent about $13,000 just on equipment, including the replacement frame and new customized grips that keep her hands on her bike. And she’s definitely not the only one. Too often, athletes with disabilities run into similar issues when a seemingly simple fix turns into a financial ordeal that can make or break their careers.

“I think people tend to forget just how unique Paralympic sport is due to us having to suit these machines to fit our disabilities,” Brim says. “The costs add up quick.”

Paralympic athletes often struggle financially.

In recent years, a growing number of elite-level athletes have spoken out about how hard it is to afford their general living expenses while they train to compete at the highest level. Former competitors have shared their experiences applying for food stamps and living close to the poverty line. A 2020 survey by Global Athlete found that of nearly 500 athletes across 48 countries, including current and former Olympians and Paralympians, 58% did not consider themselves financially stable; some said that the only way they can make their rent is “to sell possessions on eBay,” while others said that their parents still have to help them pay for their food.

The conversation picked up even more steam during the 2024 Games, thanks in part to rapper Flavor Flav. Along with sponsoring the US Women’s Water Polo team—he saw a player’s Instagram post in May that said most Olympians need a second or third job to afford to compete at their level, and was inspired to sign a five-year deal to support both the men’s and women’s national teams. He also helped pay the rent of 24-year-old discus thrower Veronica Fraley, who tweeted on August 1 that she couldn’t afford it while in Paris, and he has shared several other athletes’ GoFundMe pages.

And it’s even harder for elite athletes with disabilities to play and compete in the sports they love, thanks to highly customized sports equipment, unique travel needs, specialized health care, and limited funding and sponsorship opportunities. Several Paralympians told SELF that these steep costs often prevent athletes from ever reaching Paralympian status and young people from entering parasports altogether.

Kate Brim competing in her handcycle.

Courtesy of Joe Kusumoto/USOPC

Brim’s handcycle, for example, costs upwards of $20,000 to be race-ready. The bucket of her frame is built a bit deeper than a standard bike to hold her in, and, because she shifts gears with her head rather than her hands, two buttons are added that sit behind her ears and help her do that. “People just don’t understand how expensive it is and how much time and energy it takes from the team around us in order to be able to get those things done,” Brim says. “It’s a huge burden on athletes.”

Becca Murray, 34, a three-time Team USA Paralympic basketball player, tells SELF that she has to work a full-time job as a support coordinator for a mental health clinic to pay her mortgage and other bills. But she says this is only possible because her employer supports a flexible work schedule that allows her to practice. For a lot of athletes, though, it’s not easy or possible to work full-time while training for the Games. Paralympic sitting volleyball player Nicky Nieves told The Washington Post in 2021 that some athletes save their PTO just to compete in events that can last as long as two weeks, leaving little time for necessary rest.

Athlete stipends vary and are not guaranteed.

Most of the time, athletes with disabilities pay for everything themselves. But those who eventually make it to their national teams may receive stipends to help offset training, equipment, and travel costs. (National teams are chosen yearly, biannually, or on an ongoing basis depending on the sport and are stepping stones for athletes to join their respective Paralympic teams.) That said, it’s unclear if all of these athletes are paid; the US National Olympic and Paralympic Committee (USOPC) did not respond to SELF’s request for comment. None of the athletes who spoke to SELF were willing to share what they make, if anything. Luckily, Brim says this support helped pay for her frame repair. But not every athlete gets the same amount.

Monthly stipends are based on the tier athletes qualify for, Brim says, which is determined by their performance. So those that are put into the National A Level, for example, make more than those in the National C Level. Depending on the sport and specific event, Paralympians can also make some money based on how they place in their competitions, “but it’s not guaranteed income,” Brim says. “You could either have the best race of your life or you could get a flat tire and not be able to compete anymore,” she says. “So yeah, it’s a risky sport, financially, for sure.”

Becca Murray in a basketball tournament.

Courtesy of Ryan Kusumoto

Murray says that she gets “a little bit of money” in the form of a national team quarterly stipend to help pay for things like gym space, wheelchair parts, and workout equipment, “but it’s nothing that we would be able to live off of.” Each basketball wheelchair is at least a couple thousand dollars, Murray says, and it’s “pretty much impossible to get insurance to pay” for it when it’s hard enough to get coverage for her everyday wheelchair.

Roxanne Trunnell, 39, a three-time Paralympic equestrian who entered the Tokyo Games as the highest-ranked para-dressage athlete in the world, says she only makes money if she wins a medal. (Team USA athletes at both the Paralympics and Olympics receive $37,500 for each gold medal they win, $22,500 for every silver, and $15,000 for each bronze.) Trunnell tells SELF that she’s fortunate enough to have a sponsor who owns and cares for the horses she competes on, so that “frees me and my parents up financially to take care of my travel” and other expenses, she says. Dressage is a notoriously expensive sport, even if you don’t have a disability. Championship-level horses can cost anywhere from $50,000 to $250,000, which doesn’t include fees for vet visits, physical therapy sessions, grooming, housing, etc; meanwhile, saddles can cost about $7,000. And riders with disabilities can have additional expenses to customize this equipment to their bodies’ needs.

Trunnell owns an embroidery business called Roxifi Embroidery that appeals mostly to the horse community and provides her with an income. She makes blankets, saddle pads, ice boots, standing wraps, as well as shirts and sweaters, “basically anything I can hoop and get a needle through,” Trunnell says, because “if you want to play in the sandbox with the big boys, then you’re going to have to pay.”

Roxanne Trunnell competing in a para-dressage event.

Courtesy of Lindsay McCall

Carly Weilminster, senior director of sport communications and social media for the US Equestrian Federation (USEF), tells SELF that equestrian doesn’t have a national team, so athletes aren’t paid stipends, but they can receive funding and grants “based on performance and experience” to offset costs associated with international travel and competitions. The same is true of Paralympians in other sports, who can apply for a variety of grants and funding that the USOPC and third-party organizations offer. But some of those who spoke to SELF say these opportunities are limited, not advertised well, and still aren’t enough to cover their expenses. (The USOPC, unlike other national Olympic and Paralympic committees, doesn’t receive government financial support and is funded entirely by donations from fans and sponsorships from commercial partners.)

Travel-related mishaps aren’t easy to recover from.

Getting to competitions as a disabled athlete also poses pretty big financial risks. Brim says that nearly every time she travels with a team, at least one person’s chair is lost or damaged, despite offering airport staff detailed instructions about how to handle the equipment. “It’s a huge bummer, and we want to see change around it because it’s just so uncalled for.”

Brian Siemann, 34, a three-time track-and-field Paralympian, agrees. He says that airport staff need better training on how to transport and store wheelchairs because they can take thousands of dollars and several months to replace. “A mobility device should be in a completely different category of concern than someone’s suitcase,” he tells SELF. When Siemann travels via plane, he can box up his roughly $15,000 racing chair pretty well to avoid damage, but he can’t do that with his everyday chair because he needs it as soon as he gets off a plane. (Wheelchairs can be taken on planes if they aren’t motorized and can fit in overhead bins or other designated areas inside the cabin, but if they don’t fit they are placed in the cargo portion of the plane with checked luggage.)

Siemann’s everyday chair costs about $7,000 because it’s customized to his body, but his insurance considers that “a luxury,” meaning it’s close to impossible to get it covered. So when an airport in Miami lost it and offered $100 as an apology, it was a “jarring experience,” to say the least, he says. “There’s always a higher than likely chance that some part of your mobility device is going to be lost or damaged, which then completely impairs and restricts your ability to get around safely,” Siemann says. “And it’s not a quick fix for anyone,” particularly when sports equipment is involved.

Healthcare can get tricky and expensive for athletes with disabilities.

It’s also more challenging—physically, yes, but also financially—for a lot of Paralympic athletes to keep themselves healthy compared to their Olympic peers. Some disabilities often require regular medical attention and can make athletes more vulnerable to illnesses or stress because of the traumatic events or underlying conditions that cause them—all of which can get expensive, especially in countries like the US that don’t have universal health care.

Shortly after Brim competed at her Paralympic Trials this summer, she came down with a “pretty serious” urinary tract infection that affected her kidneys and stomach and kept her in the hospital for two weeks. That, plus the stress leading up to the event, partly triggered by her broken bike, had a huge impact. “Being able to stay healthy throughout our travels and endeavors is a lot more difficult than the everyday population,” she says. “It was a huge eye-opener for me, just how much we take for granted and how careful we have to be with ourselves in order to do the things that we love.”

Brian Siemann during a racing event.

Courtesy of Marcus Hartmann/USOPC

Necessary changes are in the works.

Some things do seem to be improving. In 2018, the USOPC (which was just the USOC at the time; the “P” wasn’t added for another year) decided to finally award Paralympians the same amount of money for the medals they win that Olympians do—a decision that came 58 years after the first Paralympics took place in Rome in 1960.

There also seem to be more opportunities for Paralympians to receive funding from sources outside their national teams and the USOPC. “Many more mainstream sponsors have become involved with the Para movement in recent years,” Weilminster of the USEF tells SELF, “and athletes now are receiving endorsement opportunities that didn’t exist in the sport previously.”

Still, challenges of all kinds persist, and the athletes who spoke to SELF say that none of it would be possible without help from their loved ones, coaches, and medical team. “I’ve been very fortunate that the support I have has been able to fuel my mission of showing people what is possible out there,” Brim says. “It takes a team to make the dream work.”

Related: